One Day/One Thing

The beauty in every small thing

Friday 19th January

THE BREATH IS LIFE'S TEACHER

Donna MartinObserve me, says the Breath, and learn to live effortlessly in the Present Moment.

Feel me, says the Breath, and feel the Ebb and Flow of Life.

Allow me, says the Breath, and I’ll sustain and nourish you, filling you with energy and cleansing you of tension and fatigue.Move with me, says the Breath, and I’ll invite your soul to dance.

Make sounds with me and I shall teach your soul to sing.

Follow me, says the Breath, and I’ll lead you out to the farthest reaches of the Universe, and inward to the deepest parts of your inner world.Notice, says the Breath, that I am as valuable to you coming or going… that every part of my cycle is as necessary as another… that after I’m released, I return again and again… that even after a long pause – moments when nothing seems to happen – eventually I am there.Each time I come, says the Breath, I am a gift from Life. And yet you release me without regret… without suffering… without fear.

Notice how you take me in, invites the Breath. Is it with joy… with gratitude…? Do you take me in fully… invite me into all the inner spaces of your home? …Or carefully into just inside the door? What places in you am I not allowed to nourish?And notice, says the Breath, how you release me. Do you hold me prisoner in closed up places in the body? Is my release resisted… do you let me go reluctantly, or easily?And are my waves of Breath, of Life, as gentle as a quiet sea, softly smoothing sandy stretches of yourself….? Or anxious, urgent, choppy waves…? Or the crashing tumult of a stormy sea…?And can you feel me as the link between your inner and outer worlds… feel me as Life’s exchange between the Universe and You? The Universe breathes me into You… You send me back to the Universe. I am the flow of life between every single part and the Whole.Your attitude to me, says the Breath, is your attitude to Life. Welcome me… embrace me fully. Let me nourish you completely, then set me free. Move with me, dance with me, sing with me, sigh with me… Love me. Trust me. Don’t try to control me.I am the Breath.

Life is the Musician.

You are the flute.

And music – creativity – depends on all of us. You are not the Creator… nor the Creation.

We are all a part of the process of Creativity… You, Life, and me: the Breath.

Sunday 14th January

Small Blue Thing

Suzanne Vega

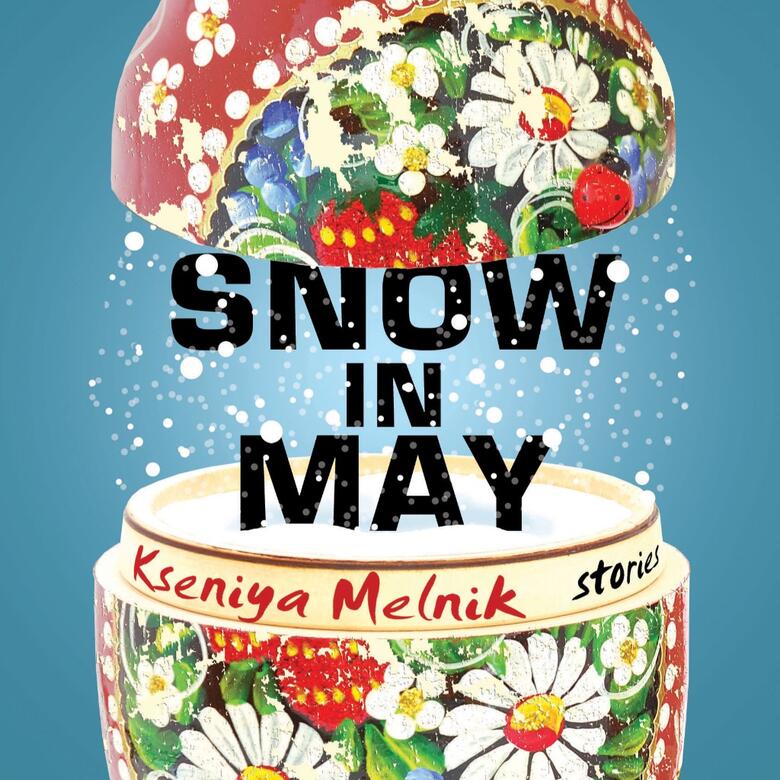

Sunday 26th November

FIRST SNOW

Mary OliverThe snow

began here

this morning and all day

continued, its white

rhetoric everywhere

calling us back to why, how,

whence such beauty and what

the meaning; such

an oracular fever! flowing

past windows, an energy it seemed

would never ebb, never settle

less than lovely! and only now,

deep into night,

it has finally ended.

The silence

is immense,

and the heavens still hold

a million candles; nowhere

the familiar things:

stars, the moon,

the darkness we expect

and nightly turn from. Trees

glitter like castles

of ribbons, the broad fields

smolder with light, a passing

creekbed lies

heaped with shining hills;

and though the questions

that have assailed us all day

remain-not a single

answer has been found-

walking out now

into the silence and the light

under the trees,

and through the fields,

feels like one.

Friday 24th November

I Have Never Loved Someone

My Brightest Diamond

Wednesday 15th November

The Precious Human Birth

Excerpt from The Book of Awakening

Mark NepoOf all the things that exist,

we breathe and wake and turn it into song.There is a Buddhist precept that asks us to be mindful of how rare it is to find ourselves in human form on earth. It is really a beautiful view of life that offers us the chance to feel enormous appreciation for the fact that we are here as individual spirits filled with consciousness, drinking water and chopping wood.It asks us to look about at the ant and antelope, at the worm and the butterfly, at the dog and the castrated bull, at the hawk and the wild lonely tiger, at the hundred year old oak and the thousand year old patch of ocean. It asks us to understand that no other life form has the consciousness of being that we are privilege to. It asks us to recognize that, of all the endless species of plant and animal and mineral that make up the earth, a very small portion of life has the wakefulness of spirit that we call being human.That I can rise from some depth of awareness to express this to you and that you can receive me in this instant is part of our precious human birth. You could have been an ant. I could have been an ant-eater. You could have been rain. I could have been a lick of salt. But we were blessed—in this time, in this place—to be human beings, alive in rare ways we often take for granted.All of this to say, this precious human birth is unrepeatable. So what will you do today, knowing that you are one of the rarest forms of life to ever walk the earth? How will you carry yourself? What will you do with your hands? What will you ask and of whom?Tomorrow you could die and become an ant, and someone will be setting traps for you. But today you are precious and rare and awake. It ushers us into grateful living. It makes hesitation useless. Grateful and awake, ask what you need to know now. Say what you feel now. Love what you love now.- Sit outside, if possible, or near a window, and note the other life forms around you.

- Breathe slowly and think of the ant and the blade of grass and the bluejay and what these life forms can do that you can’t.

- Think of the pebble and the piece of bark and the stone bench, and center your breathing on the interior things that you can do that they can’t.

- Rise slowly, feeling beautifully human, and enter your day with the conscious intent of doing one thing that only humans can do.

- When the time arises, do this one thing with great reverence and gratitude.

Friday 27th October

When we get By

Frazey Ford

Wednesday 25th October

Near Light

Ólafur Arnalds

Sunday 22nd October

Dr. Tererai Trent

Reigniting Dreams and Empowering Women

The Good Life Project

Tuesday 17th October

Catching Song

Bobby McFerrin

In Conversation with Krista Tippett | On BeingUm, improvisation basically is simply motion. It precedes musical knowledge or understanding about anything. It’s simply the act — the courageous act of opening up your mouth or putting your fingers on a keyboard or whatever — of opening your mouth and simply singing something and following it. Probably the best exercise I can think of is, you know, to tell my students to put on some kind of a timer set it for 10 minutes — open up their mouth and sing for 10 minutes, which is unbelievable how difficult that is to do for a lot of people …MS. TIPPETT: Right.MR. MCFERRIN: … because somewhere within the first two minutes of this exercise, they are going to start talking to themselves and telling themselves how stupid this is and how dumb it is. And they start thinking about how, you know, whether they are singing in tune or not or how crazy they might be sounding and, “I’m glad that there’s no one else around to listen to me sing because they’d think I was crazy” — and all that kind of stuff. And I tell them to fight all the tendencies to stop because you are going to want to. Two minutes into it, three minutes into it, eight minutes into it, you are going to want to stop. Your entire being, your body is going to be screaming, “Stop. Let me off of this,” you know.MS. TIPPETT: Right.MR. MCFERRIN: And I say no. Continue at 10 minutes and do it. Do it everyday for about three weeks and see what happens. It’s simply motion, just the courage to keep moving just to keep going, you know. What gets in the way is, you know: Am I qualified to do this? Do I know enough to do this? Do I sound well enough to do this — or whatever, you know. There are all kinds of excuses for you not to do it. Improvisation, I think, is so essential to having a well-rounded musical life.

Sunday 15th October

Encountering Grief

Joan HalifaxA guided 10 minute meditation on encountering grief — grief as something ordinary, part of life and humanity.

Friday 13th October

Ceiling Gazing

Mark Kozelek & Jimmy LaValleLaying in my bed ceiling gazing

Wide awake with jet lag from Australia

Got a stack of mail and a wedding invitation

From a new, young relative, I've never even knew ofGot me thinking about my Grandpa for some reason

Met him half a dozen times in the nursing home

Last time I saw him he was in a box

And they were lowering him into the groundSt. Mary's Church stood so high

It was the first and the last time I saw my Dad cry

The ground had a thin coat of snow

And I wandered off in the coldIt's 3:47 am, June 13th

It's my sister's birthday today, I think

I wanna give her a call, see how she's doing

She had a rough divorce, I hope she's improvedI want to reach out and give her my love

Put a smile on her face like when we were young

Listening to records from the library

Hermit of Mink Hollow and Dreamboat AnnieShe lives with her daughters all alone

Across the street from a cornfield in Ohio

One's 4, one's 7 and I love them so

I want to live a long time and see them growOutside my window tonight,

Sausalito's twinkling lights

My love's beside me deep asleep

The dog is laying between my feetOutside my window tonight

The cargo ships are cruising by

And I'm so happy to be alive

To have these people in my lifeLaying in my bed ceiling gazing

Can't make my mind stop from racing

It's not good or bad, it's just how God made me

To lay awake at night ceiling gazing

Saturday 30th September

Labouring and Resting

Karine Polwart

Monday 25th September

Seasonal Hero

Orlando Weeks with Paul Whitehouse

From The Gritterman

Saturday 23rd September

Allah Elohim

Shye Ben Tzur, Jonny Greenwood & The Rajasthan Express

Monday 11th September

Kindness

NAOMI SHIHABBefore you know what kindness really is

you must lose things,

feel the future dissolve in a moment

like salt in a weakened broth.

What you held in your hand,

what you counted and carefully saved,

all this must go so you know

how desolate the landscape can be

between the regions of kindness.

How you ride and ride

thinking the bus will never stop,

the passengers eating maize and chicken

will stare out the window forever.Before you learn the tender gravity of kindness,

you must travel where the Indian in a white poncho

lies dead by the side of the road.

You must see how this could be you,

how he too was someone

who journeyed through the night with plans

and the simple breath that kept him alive.Before you know kindness as the deepest thing inside,

you must know sorrow as the other deepest thing.

You must wake up with sorrow.

You must speak to it till your voice

catches the thread of all sorrows

and you see the size of the cloth.Then it is only kindness that makes sense anymore,

only kindness that ties your shoes

and sends you out into the day to mail letters and purchase bread,

only kindness that raises its head

from the crowd of the world to say

It is I you have been looking for,

and then goes with you everywhere

like a shadow or a friend.

Sunday 10th September

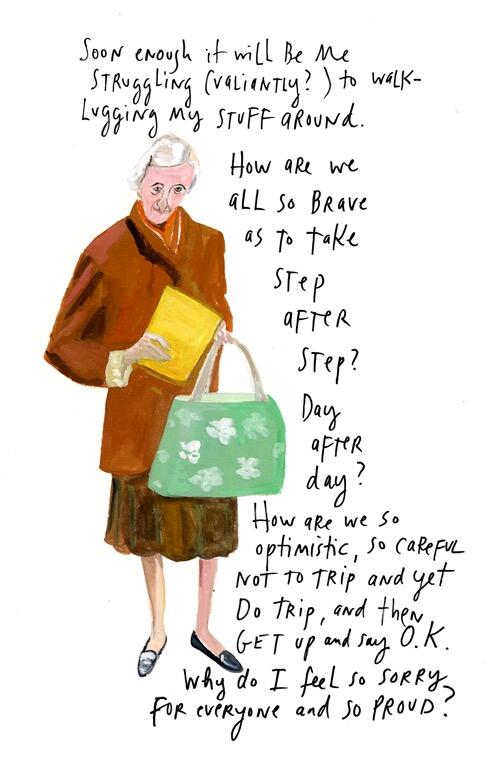

Maira Kalman

The Normal, Daily things that we fall in Love with.A podcast interview with Krista Tippett of On Being

Saturday 26th August

For the love of Lucille Ball

Friday 25th August

The Little Prince

Antoine De Saint-ExuperyAn excerptThe Little Prince went to look at the roses again.“You’re not at all like my rose. You’re nothing at all yet,” he told them. “No one has tamed you and you haven’t tamed anyone. You’re the way my fox was. He was just a fox like a hundred thousand others. But I’ve made him my friend, and now he’s the only fox in all the world.”And the roses were humbled.You’re lovely, but you’re empty,” he went on. One couldn’t die for you. Of course, an ordinary passerby would think my rose looked just like you. But my rose, all on her own, is more important than all of you together, since she’s the one I’ve watered. Since she’s the one I put under glass. Since she’s the one I sheltered behind a screen. Since she’s the one for whom I killed the caterpillars (except the two or three for butterflies). Since she’s the one I listened to when she complained, or when she boasted, or even sometimes when she said nothing at all. Since she’s my rose.”And he went back to the fox.“Good-bye,” he said.“Goodbye,” said the fox. Here is my secret. It’s quite simple: One sees clearly only with the heart. Anything essential is invisible to the eyes.”“Anything essential is invisible to the eyes,” the little prince repeated, in order to remember.“It’s the time you spend on your rose that makes your rose so important.”“It’s the time I spent on my rose…,” the little prince repeated, in order to remember.“People have forgotten this truth,” the fox said. “But you mustn’t forget it. You become responsible forever for what you’ve tamed. You’re responsible for your rose…”“I’m responsible for my rose…,” the little prince repeated, in order to remember.

Thursday 24th August

A Buddhist PrayerTHE BUDDHIST METTA (LOVINGKINDNESS) PRAYER IS SIMPLE BUT PROFOUND.It starts by blessing oneself and gradually expands outward from there, eventually wishing good intentions for the entire world and all beings, even our enemies. There are many variations and translations of this prayer, but what follows is the essence of it; if we all said this prayer with sincerity at least once per week, the world could be a very different place:My heart fills with with loving kindness. I love myself. May I be happy. May I be well. May I be peaceful. May I be free.May all beings in my vicinity be happy. May they be well. May they be peaceful. May they be free.May all beings in my city be happy. May they be well. May they be peaceful. May they be free.May all beings in my state be happy. May they be well. May they be peaceful. May they be free.May all beings in my country be happy. May they be well. May they be peaceful. May they be free.May all beings on my continent be happy. May they be well. May they be peaceful. May they be free.May all beings in my hemisphere be happy. May they be well. May they be peaceful. May they be free.May all beings on planet Earth be happy. May they be well. May they be peaceful. May they be free.May my parents be happy. May they be well. May they be peaceful. May they be free.May all my friends be happy. May they be well. May they be peaceful. May they be free.May all my enemies be happy. May they be well. May they be peaceful. May they be free.May all beings in the Universe be happy. May they be well. May they be peaceful. May they be free.If I have hurt anyone, knowingly or unknowingly in thought, word or deed, I ask for their forgiveness.If anyone has hurt me, knowingly or unknowingly in thought, word or deed, I extend my forgiveness.May all beings everywhere, whether near or far, whether known to me or unknown, be happy. May they be well. May they be peaceful. May they be free.

Wednesday 23rd August

The Dance

THEODORE ROETHKEIs that dance slowing in the mind of man

That made him think the universe could hum?

The great wheel turns its axle when it can;

I need a place to sing, and dancing-room,

And I have made a promise to my ears

I'll sing and whistle romping with the bears.For the are all my friends: I saw one slide

Down a steep hillside on a cake of ice, —

Or was that in a book? I think with pride:

A caged bear rarely does the same thing twice

In the same way: O watch his body sway! mdash;

This animal remembering to be gay.I tried to fling my shadow at the moon,

The while my blood leaped with a wordless song.

Though dancing needs a master, I had none

To teach my toes to listen to my tongue.

But what I learned there, dancing all alone,

Was not the joyless motion of a stone.I take this cadence from a man named Yeats;

I take it, and I give it back again:

For other tunes and other wanton beats

Have tossed my heart and fiddled through my brain.

Yes, I was dancing-mad, and how

That came to be the bears and Yeats would know.

Tuesday 22nd August

So Much Happiness

Naomi Shihab NyeIt is difficult to know what to do with so much happiness.

With sadness there is something to rub against,

a wound to tend with lotion and cloth.

When the world falls in around you, you have pieces to pick up,

something to hold in your hands, like ticket stubs or change.But happiness floats.

It doesn’t need you to hold it down.

It doesn’t need anything.

Happiness lands on the roof of the next house, singing,

and disappears when it wants to.

You are happy either way.

Even the fact that you once lived in a peaceful tree house

and now live over a quarry of noise and dust

cannot make you unhappy.

Everything has a life of its own,

it too could wake up filled with possibilities

of coffee cake and ripe peaches,

and love even the floor which needs to be swept,

the soiled linens and scratched records . . .Since there is no place large enough

to contain so much happiness,

you shrug, you raise your hands, and it flows out of you

into everything you touch. You are not responsible.

You take no credit, as the night sky takes no credit

for the moon, but continues to hold it, and share it,

and in that way, be known.

Monday 21st August

Pina Bausch

The Fall Dance

Thursday 17th August

The Little Thief in the Pantry.

Anonymous"MOTHER dear,” said a little mouse one day, “I think the people in our house must be very kind; don’t you? They leave such nice things for us in the larder.”There was a twinkle in the mother’s eye as she replied,—“Well, my child, no doubt they are very well in their way, but I don’t think they are quite as fond of us as you seem to think. Now remember, Greywhiskers, I have absolutely forbidden you to put your nose above the ground unless I am with you, for kind as the people are, I shouldn’t be at all surprised if they tried to catch you.”Greywhiskers twitched his tail with scorn; he was quite sure he knew how to take care of himself, and he didn’t mean to trot meekly after his mother’s tail all his life. So as soon as she had curled herself up for an afternoon nap he stole away, and scampered across the pantry shelves.Ah! here was something particularly good to-day. A large iced cake stood far back upon the shelf, and Greywhiskers licked his lips as he sniffed it. Across the top of the cake there were words written in pink sugar; but as Greywhiskers could not read, he did not know that he was nibbling at little Miss Ethel’s birthday cake. But he did feel a little guilty when he heard his mother calling. Off he ran, and was back in the nest again by the time his mother had finished rubbing her eyes after her nap.She took Greywhiskers up to the pantry then, and when she saw the hole in the cake she seemed a little annoyed.“Some mouse has evidently been here before us,” she said, but of course she never guessed that it was her own little son.The next day the naughty little mouse again popped up to the pantry when his mother was asleep; but at first he could find nothing at all to eat, though there was a most delicious smell of toasted cheese.Presently he found a dear little wooden house, and there hung the cheese, just inside it.In ran Greywhiskers, but, oh! “click” went the little wooden house, and mousie was caught fast in a trap.When the morning came, the cook, who had set the trap, lifted it from the shelf, and then called a pretty little girl to come and see the thief who had eaten her cake.“What are you going to do with him?” asked Ethel.“Why, drown him, my dear, to be sure.”The tears came into the little girl’s pretty blue eyes.“You didn’t know it was stealing, did you, mousie dear?” she said.“No,” squeaked Greywhiskers sadly; “indeed I didn’t.”Cook’s back was turned for a moment, and in that moment tender-hearted little Ethel lifted the lid of the trap, and out popped mousie.Oh! how quickly he ran home to his mother, and how she comforted and petted him until he began to forget his fright; and then she made him promise never to disobey her again, and you may be sure he never did.

Wednesday 16th August

The Peace of Wild Things

WENDELL BERRYWhen despair for the world grows in me

and I wake in the night at the least sound

in fear of what my life and my children's lives may be,

I go and lie down where the wood drake

rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.

I come into the peace of wild things

who do not tax their lives with forethought

of grief. I come into the presence of still water.

And I feel above me the day-blind stars

waiting with their light. For a time

I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.

Saturday 17th June 2017

Enrique Martinez CelayaToday [it] is very difficult to know what an artist is. I think there’s a tremendous confusion, the consciousness of an artist, what an artist is and [what is] his or her role…[is] you know very murky. And they’re murky because there’s a cynical condition in society as a whole that permeates the arts and the arts have found that the only way for the artist to have a…role that they can…sort of put themselves in is the role of the jester, of the role of the impresario – a big sort of successful artist with 20 assistants making it work or some sort of comedic entertainment figure…”“We need artists more than ever to to be the conscience of the moment to reflect back to us in a mirror what this society and what this moment is so we can see it because we cannot see it because of these creations and fabrications and reality TV [which] makes it so difficult for us to see what we’re going through…

Friday 16th June 2017

Undercover

Susanne Sundfør

Thursday 15th June 2017

Happy Endings

Margaret AtwoodJohn and Mary meet.

What happens next?

If you want a happy ending, try A.A.

John and Mary fall in love and get married. They both have worthwhile and remunerative jobs which they find stimulating and challenging. They buy a charming house. Real estate values go up. Eventually, when they can afford live-in help, they have two children, to whom they are devoted. The children turn out well. John and Mary have a stimulating and challenging sex life and worthwhile friends. They go on fun vacations together. They retire. They both have hobbies which they find stimulating and challenging. Eventually they die. This is the end of the story.B.

Mary falls in love with John but John doesn't fall in love with Mary. He merely uses her body for selfish pleasure and ego gratification of a tepid kind. He comes to her apartment twice a week and she cooks him dinner, you'll notice that he doesn't even consider her worth the price of a dinner out, and after he's eaten dinner he fucks her and after that he falls asleep, while she does the dishes so he won't think she's untidy, having all those dirty dishes lying around, and puts on fresh lipstick so she'll look good when he wakes up, but when he wakes up he doesn't even notice, he puts on his socks and his shorts and his pants and his shirt and his tie and his shoes, the reverse order from the one in which he took them off. He doesn't take off Mary's clothes, she takes them off herself, she acts as if she's dying for it every time, not because she likes sex exactly, she doesn't, but she wants John to think she does because if they do it often enough surely he'll get used to her, he'll come to depend on her and they will get married, but John goes out the door with hardly so much as a good-night and three days later he turns up at six o'clock and they do the whole thing over again.

Mary gets run-down. Crying is bad for your face, everyone knows that and so does Mary but she can't stop. People at work notice. Her friends tell her John is a rat, a pig, a dog, he isn't good enough for her, but she can't believe it. Inside John, she thinks, is another John, who is much nicer. This other John will emerge like a butterfly from a cocoon, a Jack from a box, a pit from a prune, if the first John is only squeezed enough.

One evening John complains about the food. He has never complained about her food before. Mary is hurt.

Her friends tell her they've seen him in a restaurant with another woman, whose name is Madge. It's not even Madge that finally gets to Mary: it's the restaurant. John has never taken Mary to a restaurant. Mary collects all the sleeping pills and aspirins she can find, and takes them and a half a bottle of sherry. You can see what kind of a woman she is by the fact that it's not even

whiskey. She leaves a note for John. She hopes he'll discover her and get her to the hospital in time and repent and then they can get married, but this fails to happen and she dies.

John marries Madge and everything continues as in A.C.

John, who is an older man, falls in love with Mary, and Mary, who is only twenty-two, feels sorry for him because he's worried about his hair falling out. She sleeps with him even though she's not in love with him. She met him at work. She's in love with someone called James, who is twenty-two also and not yet ready to settle down.

John on the contrary settled down long ago: this is what is bothering him. John has a steady, respectable job and is getting ahead in his field, but Mary isn't impressed by him, she's impressed by James, who has a motorcycle and a fabulous record collection. But James is often away on his motorcycle, being free. Freedom isn't the same for girls, so in the meantime Mary spends Thursday evenings with John. Thursdays are the only days John can get away.

John is married to a woman called Madge and they have two children, a charming house which they bought just before the real estate values went up, and hobbies which they find stimulating and challenging, when they have the time. John tells Mary how important she is to him, but of course he can't leave his wife because a commitment is a commitment. He goes on about this more than is necessary and Mary finds it boring, but older men can keep it up longer so on the whole she has a fairly good time.

One day James breezes in on his motorcycle with some top-grade California hybrid and James and Mary get higher than you'd believe possible and they climb into bed. Everything becomes very underwater, but along comes John, who has a key to Mary's apartment. He finds them stoned and entwined. He's hardly in any position to be jealous, considering Madge, but nevertheless he's overcome with despair. Finally he's middle-aged, in two years he'll be as bald as an egg and he can't stand it. He purchases a handgun, saying he needs it for target practice-- this is the thin part of the plot, but it can be dealt with later--and shoots the two of them and himself.

Madge, after a suitable period of mourning, marries an understanding man called Fred and everything continues as in A, but under different names.D.

Fred and Madge have no problems. They get along exceptionally well and are good at working out any little difficulties that may arise. But their charming house is by the seashore and one day a giant tidal wave approaches. Real estate values go down. The rest of the story is about what caused the tidal wave and how they escape from it. They do, though thousands drown, but Fred and Madge are virtuous and grateful, and continue as in A.E.

Yes, but Fred has a bad heart. The rest of the story is about how kind and understanding they both are until Fred dies. Then Madge devotes herself to charity work until the end of A. If you like, it can be "Madge," "cancer," "guilty and confused," and "bird watching."F.

If you think this is all too bourgeois, make John a revolutionary and Mary a counterespionage agent and see how far that gets you. Remember, this is Canada. You'll still end up with A, though in between you may get a lustful brawling saga of passionate involvement, a chronicle of our times, sort of.

You'll have to face it, the endings are the same however you slice it. Don't be deluded by any other endings, they're all fake, either deliberately fake, with malicious intent to deceive, or just motivated by excessive optimism if not by downright sentimentality.

The only authentic ending is the one provided here:

John and Mary die. John and Mary die. John and Mary die.

So much for endings. Beginnings are always more fun. True connoisseurs, however, are known to favor the stretch in between, since it's the hardest to do anything with.

That's about all that can be said for plots, which anyway are just one thing after another, a what and a what and a what.

Now try How and Why.

Wednesday 14th June 2017

It's the Dream

Olav H. HaugeIt's the dream we carry in secret

that something miraculous will happen,

that it must happen –

that time will open

that the heart will open

that doors will open

that the mountains will open

that springs will gush –

that the dream will open,

that one morning we will glide into

some little harbour we didn't know was there.

Tuesday 13th June 2017

THE IRON MAN

Ted HughesThe Coming of the Iron ManThe Iron Man came to the top of the cliff.

How far had he walked? Nobody knows. Where did he come from? Nobody knows. How was he made? Nobody knows.

Taller than a house, the Iron Man stood at the top of the cliff, on the very brink, in the darkness.

The wind sang through his iron fingers. His great iron head, shaped like a dustbin but as big as a bedroom, slowly turned to the right, slowly turned to the left. His iron ears turned, this way, that way. He was hearing the sea. His eyes, like headlamps, glowed white, then red, then infrared, searching the sea. Never before had the Iron Man seen the sea.

He swayed in the strong wind that pressed against his back. He swayed forward, on the brink of the high cliff.

And his right foot, his enormous iron right foot, lifted - up, out into space, and the Iron Man stepped forward, off the cliff, into nothingness.

CRRRAAAASSSSSSH!

Down the cliff the Iron Man came toppling, head over heels.

CRASH!

CRASH!

CRASH!

From rock to rock, snag to snag, tumbling slowly. And as he crashed and crashed and crashed.

His iron legs fell off.

His iron arms broke off, and the hands broke off the arms.

His great iron ears fell off and his eyes fell out.

His great iron head fell off.

All the separate pieces tumbled, scattered, crashing, bumping, clanging, down on to the rocky beach far below.

A few rocks tumbled with him.

Then

Silence.

Only the sound of the sea, chewing away at the edge of the rocky beach, where the bits and pieces of the Iron Man lay scattered far and wide, silent and unmoving.

Only one of the iron hands, lying beside an old, sand-logged washed-up seaman’s boot, waved its fingers for a minute, like a crab on its back. Then it lay still.

While the stars went on wheeling through the sky and the wind went on tugging at the grass on the cliff top and the sea went on boiling and booming.

Nobody knew the Iron Man had fallen.

Night passed.

Just before dawn, as the darkness grew blue and the shapes of the rocks separated from each other, two seagulls flew crying over the rocks. They landed on a patch of sand. They had two chicks in a nest on the cliff. Now they were searching for food.

One of the seagulls flew up - Aaaaaark! He had seen something. He glided low over the sharp rocks. He landed and picked something up. Something shiny, round and hard. It was one of the Iron Man’s eyes. He brought it back to his mate. They both looked at this strange thing. And the eye looked at them. It rolled from side to side looking first at one gull, then at the other. The gulls, peering at it, thought it was a strange kind of clam, peeping at them from its shell.

Then the other gull flew up, wheeled around and landed and picked something up. Some awkward, heavy thing. The gull flew low and slowly, dragging the heavy thing. Finally, the gull dropped it beside the eye. This new thing had five legs. It moved. The gull thought it was a strange kind of crab. They thought they had found a strange crab and a strange clam. They did not know they had found the Iron Man’s eye and the Iron Man’s right hand.

But as soon as the eye and the hand got together, the eye looked at the hand. Its light glowed blue. The hand stood up on three fingers and its thumb, and craned its forefinger like a long nose. It felt around. It touched the eye. Gleefully it picked up the eye, and tucked it under its middle finger. The eye peered out, between the forefinger and thumb. Now the hand could see.

It looked around. Then it darted and jabbed one of the gulls with its stiffly held finger, then darted at the other and jabbed him. The two gulls flew up into the wind with a frightened cry.

Slowly then the hand crept over the stones, searching. It ran forward suddenly, grabbed something and tugged. But the thing was stuck between two rocks. The thing was one of the Iron Man’s arms. At last the hand left the arm and went scuttling hither and thither among the rocks, till it stopped, and touched something gently. This thing was the other hand. This new hand stood up and hooked its finger round the little finger of the hand with the eye, and let itself be led. Now the two hands, the seeing one leading the blind one, walking on their fingertips, went back together to the arm, and together they tugged it free. The hand with the eye fastened itself on to the wrist of the arm. The arm stood up and walked on its hand. The other hand clung on behind as before, and this strange trio went on searching.

An eye! There it was, blinking at them speechlessly beside a black and white pebble. The seeing hand fitted the eye to the blind hand and now both hands could see. They went running among the rocks. Soon they found a leg. They jumped on top of the leg and the leg went hopping over the rocks with the arm swinging from the hand that clung to the top of the leg. The other hand clung on top of that hand. The two hands, with their eyes, guided their leg, twisting it this way and that, as a rider guides a horse.

Soon they found another leg and another arm. Now each hand, with an eye under its palm and an arm dangling from its wrist, rode on a leg separately about the beach. Hop, hop, hop , hop they went, peering among the rocks. One found an ear and at the same moment the other found the giant torso. Then the busy hands fitted the legs to the torso, then they fitted the arms, each fitting the other, and the torso stood up with legs and arms but no head. It walked about the beach, holding its eyes up in its hands, searching for its lost head. At last, there was the head - eyeless, earless, nested in a heap of read seaweed. Now in no time the Iron Man had fitted his head back, and his eyes were in place, and everything in place except for one ear. He strode about the beach searching for his lost ear, as the sun rose over the sea and the day came.

The two gulls sat on their ledge, high on the cliff. They watched the immense man striding to and fro over the rocks below. Between them, on the nesting ledge, lay a great iron ear. The gulls could not eat it. The baby gulls could not eat it. There it lay on the high ledge.

Far below, the Iron Man searched.

At last he stopped, and looked at the sea. Was he thinking the sea had stolen his ear? Perhaps he was thinking the sea had come up, while he lay scattered, and had gone down again with his ear.

He walked towards the sea. He walked into the breakers, and there he stood for a while, the breakers bursting around his knees. Then he walked in deeper, deeper, deeper.

The gulls took off and glided down low over the great iron head that was now moving slowly out through the swell. The eyes blazed red, level with the wavetops, till a big wave covered them and foam spouted over the top of the head. The head still moved out under water. The eyes and the top of the head appeared for a moment in a hollow of the swell. Now the eyes were green. Then the sea covered them and the head.

The gulls circled low over the line of bubbles that went on moving slowly out of the deep sea.

Monday 12th June 2017

Meeting Midnight

Carol Ann DuffyI met Midnight

Her eyes were sparkling pavements after frost.

She wore a full length, dark-blue raincoat with a hood.

She winked. She smoked a small cheroot.I followed her.

Her walk was more a shuffle, more a dance.

She took the path to the river, down she went.

On Midnight’s scent,

I heard the twelve cool syllables, her name,

chime from the town.

When those bells stopped,Midnight paused by the water’s edge.

She waited there.

I saw a girl in purple on the bridge.

It was One o’Clock.

Hurry, Midnight said. It’s late, it’s late.

I saw them run together.

Midnight wept.

They kissed full on the lips

And then I slept.The next day I bumped into Half-Past Four.

He was a bore.

Sunday 11th June 2017

Yoga Nidra

Saturday 10th June 2017

Nisargadatta MaharajAll you need is already within you, only you must approach your self with reverence and love. Self-condemnation and self-distrust are grievous errors. Your constant flight from pain and search for pleasure is a sign of love you bear for your self, all I plead with you is this: make love of your self perfect. Deny yourself nothing -- glue your self infinity and eternity and discover that you do not need them; you are beyond.

Friday 9th June 2017

Extract from Option B.Sherly Sandberg & Adam Grant.How to talk to a friend who is suffering.In the early weeks after Dave died, I was shocked when I’d see friends who did not ask how I was doing. I felt invisible, as if I were standing in front of them but they couldn’t see me. When someone shows up with a cast, we immediately inquire, “What happened?” If your life is shattered, we don’t.

People continually avoided the subject. I went to a close friend’s house for dinner, and she and her husband made small talk the entire time. I listened, mystified, keeping my thoughts to myself. I got emails from friends asking me to fly to their cities to speak at their events without acknowledging that travel might be more difficult for me now. Oh, it’s just an overnight? Sure, I’ll see if Dave can come back to life and put the kids to bed. I ran into friends at local parks who talked about the weather. Yes! The weather has been weird with all this rain and death.

Many people who had not experienced loss, even some very close friends, didn’t know what to say to me or my kids. Their discomfort was palpable, especially in contrast to our previous ease. As the elephant in the room went unacknowledged, it started acting up, trampling over my relationships. If friends didn’t ask how I was doing, did that mean they didn’t care? My friend and co-author Adam Grant, a psychologist, said he was certain that people wanted to talk about it but didn’t know how. I was less sure. Friends were asking, “How are you?” but I took this as more of a standard greeting than a genuine question. I wanted to scream back, “My husband just died, how do you think I am?” I didn’t know how to respond to pleasantries. Aside from that, how was the play, Mrs. Lincoln?At first, going back to work provided a bit of a sense of normalcy. But I quickly discovered that it wasn’t business as usual. I have long encouraged people to bring their whole selves to work, but now my “whole self” was just so freaking sad. As hard as it was to bring up Dave with friends, it seemed even more inappropriate at work. So I did not. And they did not. Most of my interactions felt cold, distant, stilted. In the moments when I couldn’t take it, I sought refuge with my boss Mark Zuckerberg. I told him I was worried that my personal connections with our coworkers were slipping away. He understood my fear but insisted I was misreading their reactions. He said they wanted to stay close but they did not know how.

The deep loneliness of my loss was compounded by so many distancing daily interactions that I started to feel worse and worse. I thought about carrying around a stuffed elephant but I wasn’t sure that anyone would get the hint. I knew that people were doing their best; those who said nothing were trying not to bring on more pain, those who said the wrong thing were trying to comfort. I saw myself in many of these attempts—they were doing exactly what I had done when I was on the other side.

I thought back to a friend with late-stage cancer telling me that for him the worst thing people could say was, “It’s going to be O.K.” He said the terrified voice in his head would wonder, How do you know it is going to be O.K.? Don’t you understand that I might die? I remembered the year before Dave died when a friend of mine was diagnosed with cancer. At the time, I thought the best way to offer comfort was to assure her, “You’ll be O.K. I just know it.” Then I dropped the subject for weeks, thinking she would raise it again if she wanted to.

Recently, a colleague was diagnosed with cancer and I handled it differently. I told her, “I know you don’t know yet what will happen—and neither do I. But you won’t go through this alone. I will be there with you every step of the way.” By saying this, I acknowledged that she was in a stressful and scary situation. I then continued to check in with her regularly.

As people saw me stumble at work, some of them tried to help by reducing pressure. When I messed up or was unable to contribute, they waved it off, saying, “How could you keep anything straight with all you’re going through?”

In the past, I’d said similar things to colleagues who were struggling, but when people said it to me I discovered that this expression of sympathy actually diminished my self-confidence. What helped was hearing, “Really? I thought you made a good point in that meeting and helped us make a better decision.” Bless you. Empathy was nice, but encouragement was better.

I finally figured out that I could acknowledge the elephant’s existence. At work, I told my closest colleagues that they could ask me questions and they could talk about how they felt too. One colleague said he was paralyzed when I was around, worried he might say the wrong thing. Another admitted she’d been driving by my house frequently, not sure if she should knock on the door. Once I told her that I wanted to talk to her, she finally rang the doorbell and came inside.

When people asked how I was doing, I started responding more frankly. “I’m not fine, and it’s nice to be able to be honest about that with you.” I learned that even small things could let people know that I needed help; when they hugged me hello, if I hugged them just a bit tighter, they understood that I was not O.K.

Until we acknowledge it, the elephant is always there. By ignoring it, those in pain isolate themselves and those who could offer comfort create distance instead. Both sides need to reach out. Speaking with empathy and honesty is a good place to start.

Thursday 8th June 2017

D. BunyavongPay attention to the gentle ones,

the ones who can hold your gaze with no discomfort,

the ones who smile to themselves while sitting alone in a coffeeshop,

the ones who walk as if floating.

Take them in and marvel at them. Simply marvel.

It takes an extraordinary person to carry themselves as if they do not live in hell.

Wednesday 7th June 2017

I'm Here

Rosemary & Garlic

Tuesday 6th June 2017

Life and Music

Alan WattsIn music, one doesn’t make the end of the composition the point of the composition.If that were so, the best conductors would be those who played fastest, and there would be composers who wrote only finales. People would go to concerts just to hear one crashing chord — because that’s the end!But we don’t see that as something brought by our education into our everyday conduct.We’ve got a system of schooling that gives a completely different impression. It’s all graded and what we do is we put the child into the corridor of this grade system, with a kind of, “Come on kitty kitty kitty!” and now you go to kindergarten, you know, and that’s a great thing because when you finish that you’ll get into first grade. And then — Come on! — first grade leads to second grade, and so on, and then you get out of grade school. You go to high school and it’s revving up — The thing is coming! — then you’re gonna go to college, and by jove, then you get into graduate school, and when you’re through with graduate school you go out and join the world.Then you get into some racket where you’re selling insurance, and they’ve got that quota to make and you’re gonna make that, and all the time “the thing” is coming — It’s coming, it’s coming! — that great thing: the success you’re working for.Then when you wake up one day, about 40 years old, you say, “My God, I’ve arrived! I’m there!” And you don’t feel very different from what you always felt. And there’s a slight let down because you feel there was a hoax.And there was a hoax.A dreadful hoax.They made you miss everything.We thought of life by analogy with a journey, with a pilgrimage, which had a serious purpose at the end, and the thing was to get to that end: success, or whatever it is, or maybe heaven after you’re dead.But we missed the point the whole way along.It was a musical thing — and you were supposed to sing, or dance, while the music was being played.

Monday 5th June 2017

What's the Best Thing in The World

Elizabeth BrowningWhat's the best thing in the world?

June-rose, by May-dew impearled;

Sweet south-wind, that means no rain;

Truth, not cruel to a friend;

Pleasure, not in haste to end;

Beauty, not self-decked and curled

Till its pride is over-plain;

Love, when, so, you're loved again.

What's the best thing in the world?

Something out of it, I think.

Sunday 4th June 2017

Enjoy The Silence

Eric Whitacre

Saturday 3rd June 2017

The Invitation

Oriah Mountain DreamerIt doesn't interest me

what you do for a living.

I want to know

what you ache for

and if you dare to dream

of meeting your heart's longing.It doesn't interest me

how old you are.

I want to know

if you will risk

looking like a fool

for love

for your dream

for the adventure of being alive.It doesnt interest me

what planets are

squaring your moon...

I want to know

if you have touched

the centre of your own sorrow

if have been opened

by life's betrayals

or have become shrivelled and closed

from fear of further pain.I want to know

if you can sit with pain

mine or your own

without moving to hide it

or fade it

or fix it.I want to know

if you can be with joy

mine or your own

if you can dance with wildness

and let the ecstasy fill you

to the tips of your fingers and toes

without cautioning us

to be careful

to be realistic

to remember the limitations

of being human.It doesn't interest me

if the story you are telling me

is true.

I want to know if you can

disappoint another

to be true to yourself.

If you can bear

the accusation of betrayal

and not betray your own soul.

If you can be faithless

and therefore trustworthy.I want to know if you can see Beauty

even when it is not pretty

every day.

And if you can source your own life

from its presence.I want to know

if you can live with failure

yours and mine

and still stand at the edge of the lake

and shout to the silver of the full moon,

"Yes."It doesn't interest me

to know where you live

or how much money you have.

I want to know if you can get up

after the night of grief and despair

weary and bruised to the bone

and do what needs to be done

to feed the children.It doesn't interest me

who you know

or how you came to be here.

I want to know if you will stand

in the centre of the fire

with me

and not shrink back.It doesn't interest me

where or what or with whom

you have studied.

I want to know

what sustains you

from the inside

when all else falls away.I want to know

if you can be alone

with yourself

and if you truly like

the company you keep

in the empty moments.

Friday 2nd June 2017

Enigmas

Pablo NerudaYou've asked me what the lobster is weaving there with

his golden feet?

I reply, the ocean knows this.

You say, what is the ascidia waiting for in its transparent

bell? What is it waiting for?

I tell you it is waiting for time, like you.

You ask me whom the Macrocystis alga hugs in its arms?

Study, study it, at a certain hour, in a certain sea I know.

You question me about the wicked tusk of the narwhal,

and I reply by describing

how the sea unicorn with the harpoon in it dies.

You enquire about the kingfisher's feathers,

which tremble in the pure springs of the southern tides?

Or you've found in the cards a new question touching on

the crystal architecture

of the sea anemone, and you'll deal that to me now?

You want to understand the electric nature of the ocean

spines?

The armored stalactite that breaks as it walks?

The hook of the angler fish, the music stretched out

in the deep places like a thread in the water?I want to tell you the ocean knows this, that life in its

jewel boxes

is endless as the sand, impossible to count, pure,

and among the blood-colored grapes time has made the

petal

hard and shiny, made the jellyfish full of light

and untied its knot, letting its musical threads fall

from a horn of plenty made of infinite mother-of-pearl.I am nothing but the empty net which has gone on ahead

of human eyes, dead in those darknesses,

of fingers accustomed to the triangle, longitudes

on the timid globe of an orange.I walked around as you do, investigating

the endless star,

and in my net, during the night, I woke up naked,

the only thing caught, a fish trapped inside the wind.

Thursday 1st June 2017

YouPetit Biscuit

Wednesday 31st May 2017

“A thing of beauty is a joy forever”John KeatsFrom “Endymion,” Book I.A THING of beauty is a joy forever:

Its loveliness increases; it will never

Pass into nothingness; but still will keep

A bower quiet for us, and a sleep

Full of sweet dreams, and health, and quiet breathing.

Therefore, on every morrow, are we wreathing

A flowery band to bind us to the earth,

Spite of despondence, of the inhuman dearth

Of noble natures, of the gloomy days,

Of all the unhealthy and o’er-darkened ways

Made for our searching: yes, in spite of all,

Some shape of beauty moves away the pall

From our dark spirits. Such the sun, the moon,

Trees old and young, sprouting a shady boon

For simple sheep; and such are daffodils

With the green world they live in; and clear rills

That for themselves a cooling covert make

’Gainst the hot season; the mid-forest brake,

Rich with a sprinkling of fair musk-rose blooms:

And such too is the grandeur of the dooms

We have imagined for the mighty dead;

All lovely tales that we have heard or read:

An endless fountain of immortal drink,

Pouring unto us from the heaven’s brink.

Tuesday 30th May 2017

Beauty: The Invisible Embrace

John O'DonohueWhen you become vulnerable, any ideal or perfect image of yourself falls away...Many people are addicted to perfection, and in their pursuit of the ideal, they have no patience with vulnerability...Every poet would like to write the ideal poem. Though they never achieve this, sometimes it glimmers through their best work. Ironically, the very beyondness of the idea is often the touch of presence that renders the work luminous. The beauty of the ideal awakens a passion and urgency that brings out the best in the person and calls forth the dream of excellence.The beauty of the true ideal is its hospitality towards woundedness, weakness, failure and fall-back. Yet so many people are infected with the virus of perfection. They cannot rest; they allow themselves no ease until they come close to the cleansed domain of perfection. This false notion of perfection does damage and puts their lives under great strain. It is a wonderful day in a life when one is finally able to stand before the long, deep mirror of one's own reflection and view oneself with appreciation, acceptance, and forgiveness. On that day one breaks through the falsity of images and expectations which have blinded one's spirit. One can only learn to see who one is when one learns to view oneself with the most intimate and forgiving compassion.

Monday 29th May 2017

Pure Beauty

John Baldessari“I guess the Boredom part of me is something genetic.

It’s Like having a disease you have to contain all your life .

You just got to get to your studio every day and do nothing but sweep up.

Eventually you’ll get bored and you’ll try not to be bored.

And then that’s the beginning of creativity."

Sunday 28th May 2017

Where Do You Get Your Ideas From?

Ursula K. Le Guin

From The World Split OpenA novel seldom comes from just one stimulus or “idea” but a whole

clumping and concatenation of ideas and images, visions and

mental perceptions, all slowly drawing in around some center that

is usually obscure to me until long after the book’s done and I

finally say, “Oh, that’s what that book’s about.”To me, two things are essential during this drawing together, the clumping process: before I know much of anything about the story I have to see the place, the landscape, and I have to know the principal people. By name. And it has to be the right name. If it’s the wrong name, the character won’t come to me. I won’t know who the person is. The character won’t talk, won’t do anything. Please don’t ask me how I

arrive at the name and how I know it’s the right name; I have no

idea. When I hear it, I know it. And I know who the character is,

and where. And then the story can begin.Here is an example. My book The Telling started this way: I learned that Taoist religion, an ancient popular religion of vast complexity and a major element of Chinese culture, had been suppressed, wiped out, by Mao Tse-tung. Taoism as a practice now exists chiefly in Taiwan, possibly underground on the mainland, possibly not. In one generation, one psychopathic tyrant destroyed a tradition two thousand years old. In one lifetime. My lifetime.And I knew nothing about it. The enormity of the event, and the enormity of my ignorance, left me stunned. I had to think about it. Since the way I think is fiction, eventually I had to write a story about it. But how could I write a novel about China? My poverty of experience would be fatal. A novel set on an imagined world, then, about the extinction of a religion as a deliberate political act in counterpoint to the suppression of political freedom by a theocracy? All right, there’s my theme, my idea if you will.I’m impatient to get started, impassioned by the theme. So I look for the people who will tell me the story, the people who are going to live this story. And I find this uppity kid, this smart girl who goes from Earth to that world. I don’t remember what her original name was; she had five different names. I started the book five times, and it got nowhere. I had to stop.I had to sit, patiently, and say nothing, at the same time every day, while the fox looked at me out of the corner of its eye and slowly let me get a little bit closer. And finally the woman whose story it was spoke to me. “I’m Sutty,” she said. “Follow me.” So I followed her; and she led me up into the high mountains; she gave me the book.I had a good idea; but I did not have a story. The story had to make itself, find its center, find its voice — Sutty’s voice. Then, because I was waiting for it, it could give itself to me. Or put it this way: I had a lot of stuff in my head, but I couldn’t pull it together, I couldn’t dance that dance because I hadn’t waited to catch the beat. I didn’t have the rhythm.Earlier, I used a sentence from a letter from Virginia Woolf to her

friend Vita Sackville-West. Sackville-West had been pontificating

about finding the right word, Flaubert’s mot juste, and agonizing

very Frenchly about style; and Woolf wrote back, very Englishly:As for the mot juste, you are quite wrong. Style is a very simple

matter; it is all rhythm. Once you get that, you can’t use the

wrong words. But on the other hand here am I sitting after half

the morning, crammed with ideas, and visions, and so on, and

can’t dislodge them, for lack of the right rhythm. Now this is

very profound, what rhythm is, and goes far deeper than words.

A sight, an emotion, creates this wave in the mind, long before

it makes words to fit it; and in writing (such is my present

belief) one has to recapture this, and set this working (which

has nothing apparently to do with words) and then, as it breaks

and tumbles in the mind, it makes words to fit it: But no doubt

I shall think differently next year.Woolf wrote that seventy-five years ago; if she did think differently

next year, she didn’t tell anybody. She says it lightly, but she means it: this is very profound. I have not found anything more profound, or more useful, about the source of story — where the ideas come from.Beneath memory and experience, beneath imagination and invention — beneath words, as she says — there are rhythms to which memory and imagination and words all move. The writer’s job is to go down deep enough to begin to feel that rhythm, find it, move to it, be moved by it, and let it move memory and imagination to find words.She’s full of ideas but she can’t dislodge them, she says, because she can’t find their rhythm — can’t find the beat that will unlock them, set them moving forward into a story, get them telling themselves. A “wave in the mind,” she calls it; and says that a sight or an emotion may create it, like a stone dropped into still water, and the circles go out from the center in silence, in perfect rhythm, and the mind follows those circles outward and outward till they turn to words.But her image is greater: her wave is a sea wave, traveling smooth and silent a thousand miles across the ocean till it strikes the shore and crashes, breaks, and flies up in a foam of words. But the wave, the rhythmic impulse, is before words and “has nothing to do with words.” So the writer’s job is to recognize the wave, the silent swell way out at sea, way out in the ocean of the mind, and follow it to shore, where it can turn or be turned into words, unload its story, throw out its imagery, pour out its secrets. And ebb back into the ocean of story.What is it that prevents the ideas and visions from finding their

necessary underlying rhythm, why couldn’t Woolf “dislodge” them

that morning? It could be a thousand things, distractions, worries;

but very often I think what keeps a writer from finding the words is that she grasps at them too soon, hurries, grabs. She doesn’t wait for the wave to come in and break. She wants to write because she’s a writer; she wants to say this, and tell people that, and show people something else — things she knows, her ideas, her opinions, her beliefs, important things — but she doesn’t wait for the wave to come and carry her beyond all the ideas and opinions, to where you cannot use the wrong word. None of us is Virginia Woolf, but I hope every writer has had at least a moment when they rode the wave, and all the words were right.Prose and poetry — all art, music, dance — rise from and move with the profound rhythms of our body, our being, and the body and being of the world. Physicists read the universe as a great range of vibrations, of rhythms. Art follows and expresses those rhythms. Once we get the beat, the right beat, our ideas and our words dance to it — the round dance that everybody can join. And then I am thou, and the barriers are down. For a while.

Saturday 27th May 2017

Cruel World

Active Child

Friday 26th May 2017

Lusus Naturae

Margaret Atwood

From Stone MattressWhat could be done with me, what should be done with me? These were the same question. The possibilities were limited. The family discussed them all, lugubriously, endlessly, as they sat around the kitchen table at night, with the shutters closed, eating their dry, whiskery sausages and their potato soup. If I was in one of my lucid phases I would sit with them, entering into the conversation as best I could while searching out the chunks of potato in my bowl. If not, I’d be off in the darkest corner, mewing to myself and listening to the twittering voices nobody else could hear.“She was such a lovely baby,” my mother would say. “There was nothing wrong with her.” It saddened her to have given birth to an item such as myself: it was like a reproach, a judgment. What had she done wrong?“Maybe it’s a curse,” said my grandmother. She was as dry and whiskery as the sausages, but in her it was natural because of her age.“She was fine for years,” said my father. “It was after that case of measles, when she was seven. After that.”“Who would curse us?” said my mother.My grandmother scowled. She had a long list of candidates. Even so, there was no one she could single out. Our family had always been respected, and even liked, more or less. It still was. It still would be, if something could be done about me. Before I leaked out, so to say.“The doctor says it’s a disease,” said my father. He liked to claim he was a rational man. He took the newspapers. It was he who insisted that I learn to read, and he’d persisted in his encouragement, despite everything. I no longer nestled into the crook of his arm, however. He sat me on the other side of the table. Though this enforced distance pained me, I could see his point.“Then why didn’t he give us some medicine?” said my mother. My grandmother snorted. She had her own ideas, which involved puffballs and stump water. Once she’d held my head under the water in which the dirty clothes were soaking, praying while she did it. That was to eject the demon she was convinced had flown in through my mouth and was lodged near my breastbone. My mother said she had the best of intentions, at heart.Feed her bread, the doctor had said. She’ll want a lot of bread. That, and potatoes. She’ll want to drink blood. Chicken blood will do, or the blood of a cow. Don’t let her have too much. He told us the name of the disease, which had some Ps and Rs in it and meant nothing to us. He’d only seen a case like me once before, he’d said, looking at my yellow eyes, my pink teeth, my red fingernails, the long dark hair that was sprouting on my chest and arms. He wanted to take me away to the city, so other doctors could look at me, but my family refused. “She’s a lusus naturae,” he’d said.“What does that mean?” said my grandmother. “Freak of nature,” the doctor said. He was from far away: we’d summoned him. Our own doctor would have spread rumours. “It’s Latin. Like a monster.” He thought I couldn’t hear, because I was mewing. “It’s nobody’s fault.”“She’s a human being,” said my father. He paid the doctor a lot of money to go away to his foreign parts and never come back.“Why did God do this to us?” said my mother.“Curse or disease, it doesn’t matter,” said my older sister. “Either way, no one will marry me if they find out.” I nodded my head: true enough. She was a pretty girl, and we weren’t poor, we were almost gentry. Without me, her coast would be clear.In the daytimes I stayed shut up in my darkened room: I was getting beyond a joke. That was fine with me, because I couldn’t stand sunlight. At night, sleepless, I would roam the house, listening to the snores of the others, their yelps of nightmare. The cat kept me company. He was the only living creature who wanted to be close to me. I smelled of blood, old dried‐up blood: perhaps that was why he shadowed me, why he would climb up onto me and start licking.They’d told the neighbours I had a wasting illness, a fever, a delirium. The neighbours sent eggs and cabbages; from time to time they visited, to scrounge for news, but they weren’t eager to see me: whatever it was might be catching.It was decided that I should die. That way I would not stand in the way of my sister, I would not loom over her like a fate. “Better one happy than both miserable,” said my grandmother, who had taken to sticking garlic cloves around my door frame. I agreed to this plan, I wanted to be helpful.The priest was bribed; in addition to that, we appealed to his sense of compassion. Everyone likes to think they are doing good while at the same time pocketing a bag of cash, and our priest was no exception. He told me God had chosen me as a special girl, a sort of bride, you might say. He said I was called on to make sacrifices. He said my sufferings would purify my soul. He said I was lucky, because I would stay innocent all my life, no man would want to pollute me, and then I would go straight to Heaven.He told the neighbours I had died in a saintly manner. I was put on display in a very deep coffin in a very dark room, in a white dress with a lot of white veiling over me, fitting for a virgin and useful in concealing my whiskers. I lay there for two days, though of course I could walk around at night. I held my breath when anyone entered. They tiptoed, they spoke in whispers, they didn’t come close, they were still afraid of my disease. To my mother they said I looked just like an angel.My mother sat in the kitchen and cried as if I really had died; even my sister managed to look glum. My father wore his black suit. My grandmother baked. Everyone stuffed themselves. On the third day they filled the coffin with damp straw and carted it off to the cemetery and buried it, with prayers and a modest headstone, and three months later my sister got married. She was driven to the church in a coach, a first in our family. My coffin was a rung on her ladder.Now that I was dead, I was freer. No one but my mother was allowed into my room, my former room as they called it. They told the neighbours they were keeping it as a shrine to my memory. They hung a picture of me on the door, a picture made when I still looked human. I didn’t know what I looked like now. I avoided mirrors.In the dimness I read Pushkin, and Lord Byron, and the poetry of John Keats. I learned about blighted love, and defiance, and the sweetness of death. I found these thoughts comforting. My mother would bring me my potatoes and bread, and my cup of blood, and take away the chamber pot. Once she used to brush my hair, before it came out in handfuls; she’d been in the habit of hugging me and weeping; but she was past that now. She came and went as quickly as she could. However she tried to hide it, she resented me, of course. There’s only so long you can feel sorry for a person before you come to feel that their affliction is an act of malice committed by them against you.At night I had the run of the house, and then the run of the yard, and after that the run of the forest. I no longer had to worry about getting in the way of other people and their futures. As for me, I had no future. I had only a present, a present that changed – it seemed to me – along with the moon. If it weren’t for the fits, and the hours of pain, and the twittering of the voices I couldn’t understand, I might have said I was happy.My grandmother died, then my father. The cat became elderly. My mother sank further into despair. “My poor girl,” she would say, though I was no longer exactly a girl. “Who will take care of you when I’m gone?”There was only one answer to that: it would have to be me. I began to explore the limits of my power. I found I had a great deal more of it when unseen than when seen, and most of all when partly seen. I frightened two children in the woods, on purpose: I showed them my pink teeth, my hairy face, my red fingernails, I mewed at them, and they ran away screaming. Soon people avoided our end of the forest. I peered into a window at night and caused hysterics in a young woman. “A thing! I saw a thing!” she sobbed. I was a thing, then. I considered this. In what way is a thing not a person?A stranger made an offer to buy our farm. My mother wanted to sell and move in with my sister and her gentry husband and her healthy, growing family, whose portraits had just been painted; she could no longer manage; but how could she leave me?“Do it,” I told her. By now my voice was a sort of growl. “I’ll vacate my room. There’s a place I can stay.” She was grateful, poor soul. She had an attachment to me, as if to a hangnail, a wart: I was hers. But she was glad to be rid of me. She’d done enough duty for a lifetime.During the packing up and the sale of our furniture I spent the days inside a hayrick. It was sufficient, but it would not do for winter. Once the new people had moved in, it was no trouble to get rid of them. I knew the house better than they did, its entrances, its exits. I could make my way around it in the dark. I became an apparition, then another one; I was a red‐nailed hand touching a face in the moonlight; I was the sound of a rusted hinge that I made despite myself. They took to their heels, and branded our place as haunted. Then I had it to myself.I lived on stolen potatoes dug by moonlight, on eggs filched from henhouses. Once in a while I’d purloin a hen – I’d drink the blood first. There were guard dogs, but though they howled at me, they never attacked: they didn’t know what I was. Inside our house, I tried a mirror. They say dead people can’t see their own reflections, and it was true; I could not see myself. I saw something, but that something was not myself: it looked nothing like the kind and pretty girl I knew myself to be, at heart.***But now things are coming to an end. I’ve become too visible.This is how it happened.I was picking blackberries in the dusk, at the verge where the meadow meets the trees, and I saw two people approaching, from opposite sides. One was a young man, the other a girl. His clothing was better than hers. He had shoes.The two of them looked furtive. I knew that look – the glances over the shoulder, the stops and starts – as I was unusually furtive myself. I crouched in the brambles to watch. They clutched each other, they twined together, they fell to the ground. Mewing noises came from them, growls, little screams. Perhaps they were having fits, both of them at once. Perhaps they were – oh, at last! – beings like myself. I crept closer to

see better. They did not look like me – they were not hairy, for instance, except on their heads, and I could tell this because they had shed most of their clothing – but then, it had taken me some time to grow into what I was. They must be in the preliminary stages, I thought. They know they are changing, they have sought out each other for the company, and to share their fits.They appeared to derive pleasure from their flailings about, even if they occasionally bit each other. I knew how that could happen. What a consolation it would be to me if I, too, could join in! Through the years I had hardened myself to loneliness; now I found that hardness dissolving. Still, I was too timorous to approach them.One evening the young man fell asleep. The girl covered him with his cast‐off shirt and kissed him on the forehead. Then she walked carefully away.I detached myself from the brambles and came softly towards him. There he was, asleep in an oval of crushed grass, as if laid out on a platter. I’m sorry to say I lost control. I laid my red‐nailed hands on him. I bit him on the neck. Was it lust or hunger? How could I tell the difference? He woke up, he saw my pink teeth, my yellow eyes; he saw my black dress fluttering; he saw me running away. He saw where.He told the others in the village, and they began to speculate. They dug up my coffin and found it empty, and feared the worst. Now they’re marching towards this house, in the dusk, with long stakes, with torches. My sister is among them, and her husband, and the young man I kissed. I meant it to be a kiss.What can I say to them, how can I explain myself ? When demons are required someone will always be found to supply the part, and whether you step forward or are pushed is all the same in the end. “I am a human being,” I could say. But what proof do I have of that? “I am a lusus naturae! Take me to the city! I should be studied!” No hope there. I’m afraid it’s bad news for the cat. Whatever they do to me, they’ll do to him as well.I am of a forgiving temperament, I know they have the best of intentions at heart. I’ve put on my white burial dress, my white veil, as befits a virgin. One must have a sense of occasion. The twittering voices are very loud: it’s time for me to take flight. I’ll fall from the burning rooftop like a comet, I’ll blaze like a bonfire. They’ll have to say many charms over my ashes, to make sure I’m really dead this time. After a while I’ll become an upside‐down saint; my finger bones will be sold as dark relics. I’ll be a legend, by then.Perhaps in Heaven I’ll look like an angel. Or perhaps the angels will look like me. What a surprise that will be, for everyone else! It’s something to look forward to.

Thursday 25th May 2017

When Things Fall Apart

Pema ChödrönChapter 14The Love that Will Not Die

Wednesday 24th May 2017

Ólafur Arnalds

Ljósið

Tuesday 23rd May 2017

“what they did yesterday afternoon”

Warsan Shirethey set my aunts house on fire

i cried the way women on tv do

folding at the middle

like a five pound note.

i called the boy who used to love me

tried to ‘okay’ my voice

i said hello

he said warsan, what’s wrong, what’s happened?i’ve been praying,

and these are what my prayers look like;

dear god

i come from two countries

one is thirsty

the other is on fire

both need water.later that night

i held an atlas in my lap

ran my fingers across the whole world

and whispered

where does it hurt?it answered

everywhere

everywhere

everywhere.

Monday 22nd May 2017